In 2012 and 2015, Damian Evans, an archaeologist at the French Institute of Asian Studies, conducted extensive surveys into Cambodia’s ancient temple complexes. Many of these sites had never been fully investigated due to difficult terrain. Using a technology known as LIDAR (light detection and ranging), Evans and his team were able to build up an unprecedented understanding of these ruins

Interview by Thomas Brent

How does LIDAR work and what did it help you uncover?

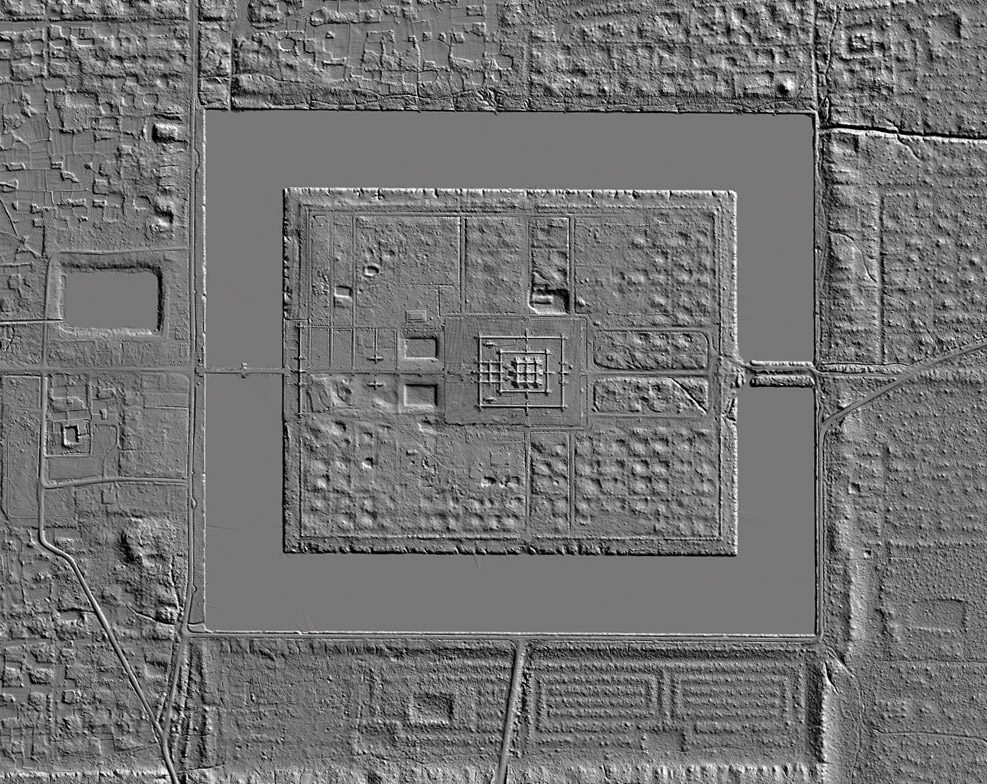

Fundamentally, the LIDAR system is just a fancy measuring device that we attach to an aircraft which measures the distance to the ground using a laser rangefinder. The lasers can find their way to the ground through tiny gaps in the vegetation, even in dense jungle. Because we know where the aircraft is in space using an on-board GPS, it’s fairly easy to calculate where the ground is in three-dimensional space as well. Together, millions or even billions of these points form a high-resolution 3D model of the landscape beneath the aircraft.

We uncovered elements of urban areas all across Cambodia in the course of these two acquisitions, mostly dating from the Angkorian period but also from before and after. Beyond the temples, cities of this period were mostly made from non-durable materials like wood, and have slowly rotted away and disappeared over the years. Fortunately, this kind of intensive human activity leaves traces on the surface of the landscape for hundreds or even thousands of years. We can see where neighbourhoods were, water management systems, networks of ponds and canals – the fabric of the cities of the people who built and lived among the well-known temples.

What are some of the major discoveries that have come from using LIDAR?

For our team, the big discoveries are to do with understanding the everyday life of the people. The media likes to sensationalise the discoveries and imagine somehow that we are uncovering “lost cities” and this kind of thing. In reality, we always assumed there were cities attached to the temples. Of course, to finally see them and know what they look like in detail is a pretty amazing thing, but to be honest, there’s not much to look at on the ground. You can be standing in the middle of it on the ground and not even know it’s there, although it does look pretty incredible on the computer screen. It provides an important window into how the cities rose and fell.

What is significant about the findings from the two LIDAR surveys?

Probably the most significant thing is to finally arrive at complete maps of pretty much every early city in the early Khmer world. These traces are under threat from urban extensification, agricultural expansion and this kind of thing, so now we have captured an archive that we can preserve forever. It provides a fascinating window into how the ancestors of contemporary Cambodians transformed their natural environments into engineered landscapes, struggling with issues like water supply, climate variation, floods, droughts and this kind of thing. This story is preserved in subtle variations in the terrain, and LIDAR gives us the capacity to read it, in a way.

What was your reaction when you saw the results of the surveys?

It is pretty amazing to see all of this unfold on the screen in front of you. It takes thousands of hours of planning and flying and processing to arrive at the point of data delivery, but once the LIDAR engineers hand you the hard drives, it’s just a few clicks of the button to arrive at a complete picture of an ancient city in breathtaking detail. Everyone crowds around the screen to see it unfold, and there’s usually a few gasps in the room from archaeologists who are on hand to see it.

This journey of scientific exploration and discovery spanning three centuries is more or less complete. You can’t help but wonder what all the people who came before us would have thought of it all. On the other hand, of course it opens up new horizons for more intensive work on the ground as well.

What can the LIDAR surveys tell us about ancient Angkor and pre-Angkorian societies?

It tells us that the temples were the centres of extensive and very well-populated urban areas. In a way, the temples that we are all familiar with mark the kind of “downtown” areas of those ancient cities. The urban networks immediately around the temples are formally planned, well-organised, and are neatly divided into city blocks divided by streets and canals. As you move progressively away from the urban core, things start to get a bit messier, there starts to be more open space and fields mixed among the residential areas, and eventually the populated areas give way to the agricultural hinterland.

When we create maps, they don’t look anything like the cities of antiquity that everyone is familiar with, with nice city walls neatly defining the limits of the inhabited space. The footprint of these places looks a lot more like the kind of urban sprawl we see in the contemporary world, actually, and can also be found in other early rainforest civilisations such as the Maya world, for example. It’s interesting because we believe that, partly because of this analogous structure, the trajectory of growth and decline of these ancient cities offers us some insight into the way in which contemporary urban environments develop and operate, and vice versa. That’s really the bigger picture of what we are doing here.

Three of Cambodia’s lesser-known temples

Banteay Chhmar

Banteay Chhmar dates from the late 12th century to early 13th century, in the time of Jayavarman VII. It is the fourth largest temple of the Angkorian period and bears architectural resemblance to the well-known Bayon Temple. It is situated around 150 km north of Siem Reap, close to the Thai border, and its remoteness makes it one of Cambodia’s best-kept secrets. Now, nature has claimed the site and tall, beautiful silver trees hang over the old ruins, adding to the sense of mystery that defines Banteay Chhmar. While the site can be visited in one day, it is worth staying overnight in a homestay in the nearby village for a complete experience.

Koh Ker

Koh Ker was built in the 10th century and dedicated to Treypuvanesvara, a Hindu god of happiness. The seven-tiered pyramid stands 35m high and thrusts out of the jungle undergrowth like a small hill. It is the main attraction of a temple complex that was once scattered with ornate temples, most now lying in ruins. Koh Ker remains incredibly well preserved, making the 55 steps it takes to reach the top worth it. It is around 120 km northeast of Siem Reap, but there are no buses or public transportation options to take visitors to the site, so it is necessary to rent a taxi or a minivan. It is a great one-day trip from Siem Reap, and can also be visited on the same day as Beng Mealea.

Beng Mealea

Beng Mealea is the mysterious 12th century temple that is lost in the greenery of nature, giving visitors the feeling of being in an adventure film. It lies 70 km from Siem Reap, making for an ideal half-day trip, or it can be combined with Koh Ker for a full-day excursion. The builder of the temple remains unknown, and there are no inscriptions alluding to their identity, lending the temple an air of intrigue that is intensified by the ruinous state of the site. It was once one of the largest temples of the Angkorian era, and, despite its slow slide into disrepair, remains an impressive sight. It’s relatively unknown, so it is worth visiting soon before the crowds discover it.

This story was originally published on Discover magazine 2019 vol.