French-trained Cambodian artist flaunts his unique style in paintings and design

It’s hard to miss Em Riem. As one of Phnom Penh’s premier artists and digital personalities, Riem is recognized equally for his paintings and signature twirled moustache. He gained renown at home and abroad for portraits of Khmer Rouge victims, a series that drew inspiration from his experience growing up under Democratic Kampuchea’s brutal regime.

In the decades since his harrowing childhood, Riem graduated from Phnom Penh’s Royal University of Fine Arts, received a master’s and PhD at the prestigious École Supérieure d’Art et Design Saint-Étienne in France, and opened his successful X-em gallery catering to the city’s increasingly international art clientele. As well as painting, Riem sculpts and designs furniture, creating wholly original designs out of traditional natural materials.

Defiantly fabulous, he has also gained notoriety for his over-the-top sense of fashion, which he flaunts on Facebook, Instagram and to his nearly 1 million TikTok followers. Though reactions are generally positive, some of his more risque looks have been disdained by high-profile members of Cambodia’s political class, resulting in a Facebook condemnation from the Ministry of Culture. Far from being a political provocateur, Riem insists his social media presence is simply a means of promoting his art, and any suggestion that he is working against Cambodian culture is missing the point.

Focus sat down with Riem to discuss inspiration and art, his country and culture, and the role of social media in his life.

After graduating from Royal University of Fine Arts, you studied in France. What made you decide to travel abroad for your education?

In Cambodian art school we practise a lot in the Angkorian style. But at the same time I turned to French culture to learn about contemporary painting, modern sculpture, contemporary sculpture. I was also working with a collective, creating art that was influenced by French culture.

Here, we respect the Angkor style, traditional painting styles that cannot be changed. But in France, you get ideas and the style will change. It’s about ideas and what you want to show people. It’s very, very different.

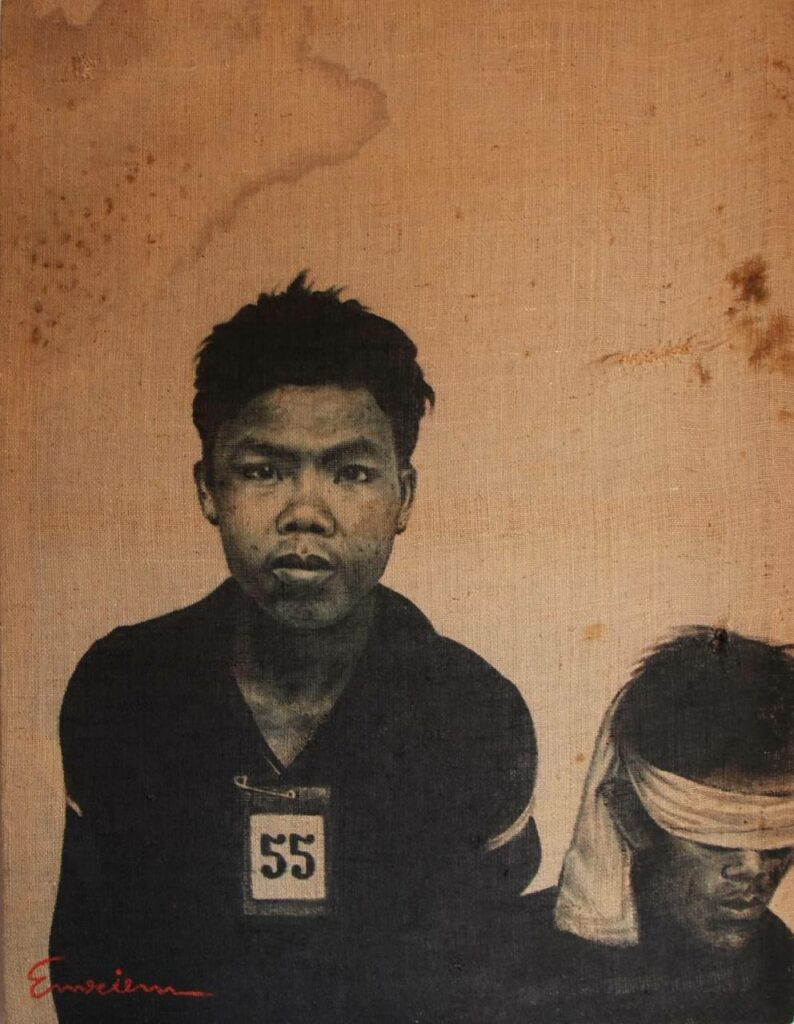

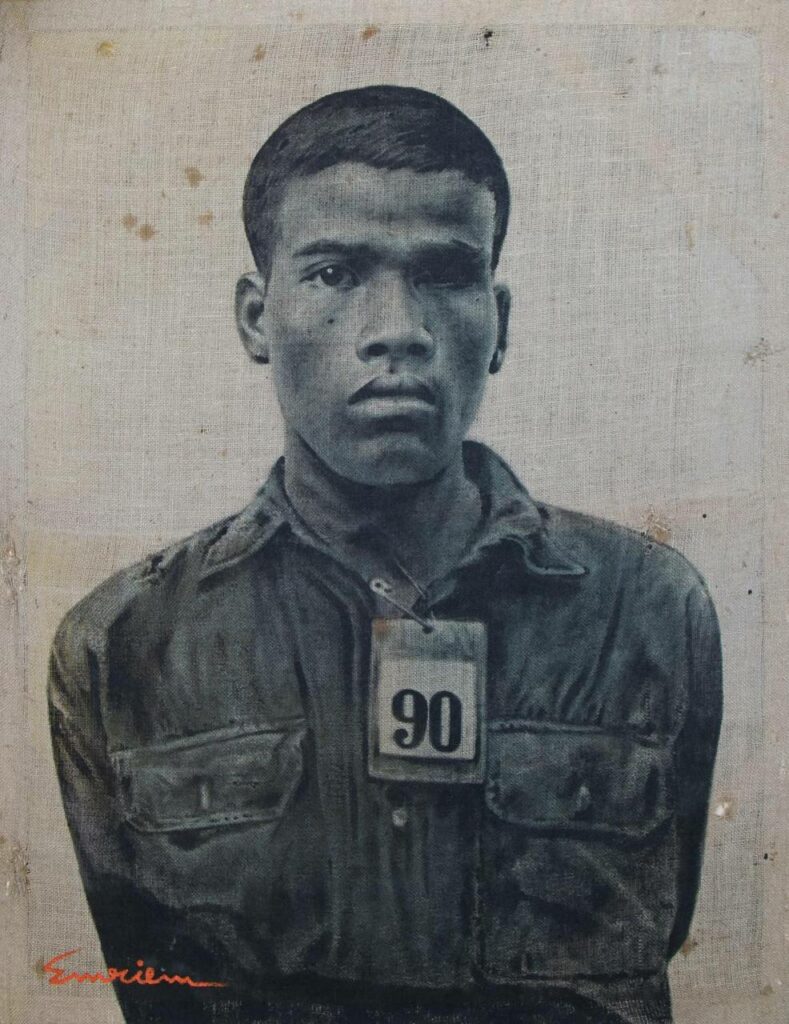

Some of your most popular work is a portrait series of Khmer Rouge victims painted onto Cambodia’s ubiquitous rice bags. What was the inspiration behind this project and what drew you to such an emotionally charged subject?

I was born in 1970, so I was four or five years old during the Khmer Rouge. I was a refugee in Battambang and grew up there. I saw a lot of death – dead animals, dead people.

But then, when I was studying in France, they would ask where I was from. I would say, “I’m from Cambodia,” but nobody knew it! I would say, “You know Angkor Wat?” They didn’t know. But when I said the Khmer Rouge, they all knew that. So, I started my project for contemporary art focused on the Khmer Rouge, painting the things I saw, skulls and other things, in a contemporary style.

When I came back to Cambodia, I continued to work with victims of the Khmer Rouge, painting their portraits. I used raw materials, rice bags from Battambang, because they are part of Cambodian life. This was a tragedy – I am not a historian, I am an artist – but it is part of the history of Cambodia, so we cannot forget.

Your paintings have garnered acclaim from local and international audiences. However, you work in a number of different mediums, from sculpture and textiles to designing unique furniture. How did you come to use rattan as a material?

My family worked a lot with wood, but in the traditional style. I went to France to make something contemporary.

Before I was not a designer, I just worked with my father and helped him make something in wood, tables and chairs. When I became a designer, I did research and learned that something like 80% of Cambodia’s forests have been destroyed. So I researched sustainable design – recycling, using plywood – but the more I researched, I went to rattan. We can plant rattan and in 5 years we can cut it and will have a lot of rattan like this [gesturing to his forearm]. If we put the rattan through a machine, it becomes like spaghetti and you can use it in many different ways.

I wanted to show people around the world and let them see that rattan is good for sustainable design. Now we have five very small factories to process rattan to make furniture.

In many ways Cambodia is still a very traditional culture. However, attitudes regarding the LGBTQ community seem to be changing, particularly in the capital. In your experience, how do you feel the LGBTQ community fits into Cambodia?

It is easier than before. Before we didn’t have Pride, it was just private events in bars or clubs. But now we can have events in public, and we can show off. Gay, straight, we can all go to have fun and support each other. Pride gives the possibility for the LGBT [community] to have events and come and have crazy styles and have support.

I support LGBT by dressing up. I just want to show a little bit of LGBT style, because in Cambodia, they still don’t like it so much. I cannot talk because I know Khmer people and the politics here. Not in Phnom Penh, but in the province, they say things, “This is not Cambodian culture, or Cambodian style, you are destroying it yadda yadda yadda.” In Phnom Penh, it’s ok. It’s for fun.

Speaking of social media and “destroying culture,” some of your Facebook posts have created a bit of controversy. Recently the Ministry of Culture stated that one revealing photo went against Cambodian culture. What’s your response to these claims?

It’s a long story. Some people don’t like my style. For me, even though I wear a lady’s dress, and I have a crazy moustache and hair, it is for marketing for my gallery. I cannot go out and just say, “Hey, I am an artist in Cambodia!” So, I go to events and people know me, this is enough. I know a lot of people don’t like it, they talk about it on Facebook.

They say this is not Khmer culture. They don’t understand fashion. At the SEA Games ceremony, I had 13 different fashions for the catwalk: Angkor style with the crown, old styles, colonial styles. But also new styles, all the different styles mixed together to create today’s style.

I am an artist, I am a fashion designer, I can wear anything. This is for my marketing and communications, not to destroy Cambodian culture. I spend a lot of money on my gallery, for what? French culture? No. For Cambodian culture. This is my way to show who I am. I am Em Riem, I can post what I want. It’s just something crazy I want to put up, I won’t stop.